Don’t be a t*sser: How to reduce littering with effective signage

The problem and the pandemic

In 2020, in the height of the pandemic, beaches in the UK saw huge amounts of litter and bags of rubbish being left by people visiting these areas. Images shared on social media and TV news were received, understandably, with anger, judgement and exasperation from the public. In a Metro article at the time, Dr Konstantinos Arfanis, a lecturer in psychology at Arden University, suggested that the pandemic had changed so many social norms that ‘social conventions (had) become irrelevant, (so) we have to learn again how to behave publicly.’ In the same article, Professor Margareta also said it could be the result of ‘a subconscious way to break out of the “forced- upon” compliance they had to adhere to’, suggesting littering could also be a sign of rebellion following the enforced lockdown.

Other factors which led to increased littering issues during the pandemic include:

- Cafes and restaurants offering takeaway service only – with many chains even banning reusables – leading to a huge increase in single-use packaging being used.

- The concentration of people using outdoor spaces meant the bin infrastructure was generally unable to cope with the volume of single-use materials.

- The impact of masks that fall out of pockets or get dropped but are not picked up by others for fear of COVID-19

Signage Case Study

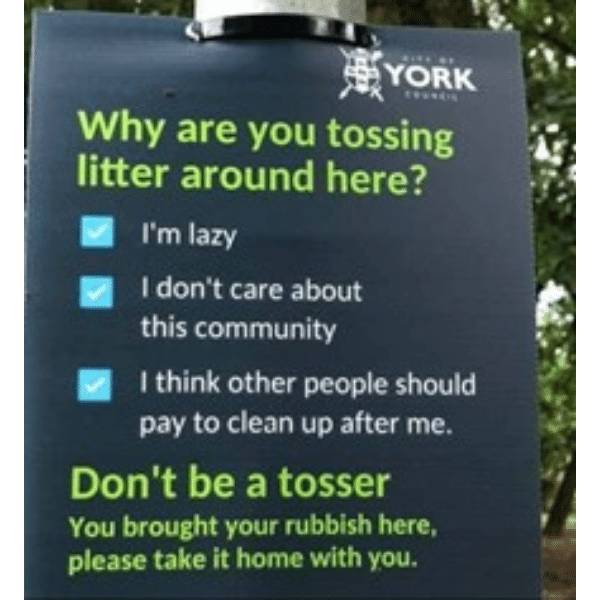

So, what can be done about this huge litter problem? Different councils tried different approaches. In 2020, York Council put up signs that asked the question ‘Why are you tossing litter around here?’ and gave multiple choice answers, followed by the slogan ‘Don’t be a tosser.’ A strong message and memorable sign, it must have had a big impact right? Well actually, no. This approach actually goes against the studied behavioural psychology around how to effectively communicate appropriate behaviours. In fact, the sign’s multiple choice options actually reinforce all the reasons why people actually litter and the message, while memorable, is unlikely to engage those who are most likely to litter. Let’s break it down:

I’m Lazy = Yes quite probably true as the human brain does a ‘cost-benefit’ analysis and if there isn’t a bin easily accessible, littering makes sense when there is no ‘benefit’ for the carrier of the item.

I don’t care about the community = Yes, again probably true as the biggest litterers are generally young people between ages of 18-34. This is often done as a sign of rebellion from wider societal expectations to fit in with their peer group and appear ‘cool’. Furthermore, humans look for cues in areas to understand what is the social norm in a particular area, so the appearance of litter suggests that it is socially acceptable. Research has shown that with 1-2 pieces of litter, (78% and 90% of people, respectively, used bins) with more than three pieces of litter, litterers increased by 41%.

I think other people should clean up after me – Yes, it’s called the ‘tragedy of the commons’. People often think their one piece of litter won’t make a difference. Plus there is a lack of sense of shared responsibility and care for public places because taxes are paid to ‘clean and maintain them’ – it’s the councils responsibility and people are paid to clean the streets, beaches etc.

You brought your rubbish here, please take it home Well true, but people don’t feel responsible for the packaging once they’ve consumed the goods. They bought the contents inside the packaging, not the packaging so they don’t value it. The fact that packaging has no value and has become ‘rubbish’ is a further tragedy of the commons. The manufacturers don’t value packaging so don’t want it back, and plastic wrappers are so thin that there is no value for recyclers. It has no value for anyone.

So, what does work??

Addressing the bin infrastructure is a good place to start, so more bins located in places where there is high incidence of littering or food consumption. Putting recycling and general waste bins together so people can dispose of all packing in the same place also helps make it easier for people.

As illustrated above, if packaging has a value then it is less likely to be littered. The introduction of deposit return schemes – this year in Scotland and next year in the rest of the UK – will go some way to address the littering problem of bottles and cans.

One of the most effective ways of reducing litter is to go straight to the source and reduce the amount of single-use materials being generated in the first place. Shrewsbury Cup is an example of a local reusable coffee cup scheme that is helping reduce the use of single-use coffee cups in Shrewsbury. Customers pay a £1 deposit for the cup which they can then return to one of many participating cafes in the local area. The more local reusable coffee and bar cup schemes that are operating, the less single-use coffee cups will be used and will end up on our streets, beaches and in our rivers and oceans. Plus it removes the need for customers to carry their own reusable cup as well as a reusable water bottle – win, win!

Signage Case Study 2

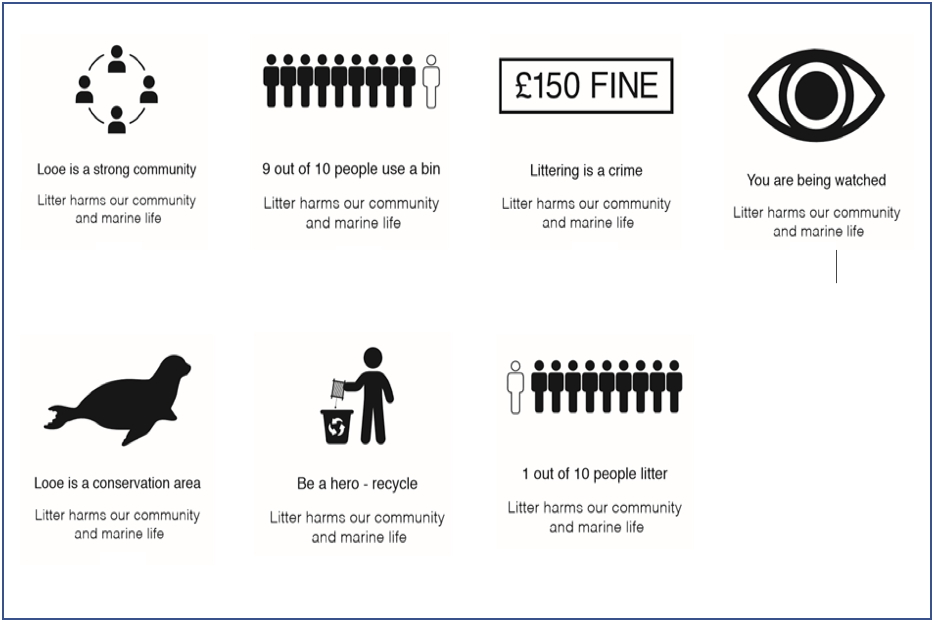

Thankfully, it is possible to reduce littering using effective signage. The Behaviour Change Cornwall ‘ Living Lab Looe’ conducted research on ‘anti-littering, pro-bin usage’ sign messaging, testing behavioural psychology and traditional methods of messaging. Here’s a breakdown of their research and findings:

They created 7 sign, each featuring an image, a short lead message based in different beahviour change principles, and the sub message ‘Litter harms our community and marine life’:

Image: Behaviour Change Cornwall https://behaviourchangecornwall.co.uk/signs-to-stop-plastic/

They then tested the effectiveness of each of the signs on reducing litter, outlined in the table below:

| Sign and lead message | Principle | Effectiveness | How else could this be used? |

|

Community image

Looe is a strong community |

Traditional social message- appealing to values. If people don’t have a relationship with the community this won’t be activated | No significant difference | |

|

£150 fine image

Littering is a crime |

Traditional threat – as these fines are rarely enforced they may lack any perceived threat | No significant difference | |

|

Seal image

Looe is a conservation area |

Traditional conservation message – appealing to environmental values.

Potentially engaging the visitors as that is part of why they are visiting. This may not work in all settings |

Significant reduction | |

|

Eye image

You are being watched |

Observation bias – humans behave differently if they think they are being observed because they care what others think about them

|

Significant reduction | This has been effectively used for littering and theft prevention |

|

Someone putting litter in the bin

Be a hero – recycle

|

Prescriptive norms- Telling us what to do, and what is expected with a positive reinforcement INSTEAD of a Proscriptive DON’T LITTER sign | Significant reduction | Be a hero- bring your reusable |

| 9 out of 10 people use a bin | Positive descriptive norm- Reinforcing the social norm with the majority of people 9 out of 10 doing the ‘ideal behaviour’. | Significant reduction | A figure for how many people carry a reusable |

| 1 out of 10 people litter | Negative Descriptive norm- Highlighting how few people litter. This is still focusing on the negative behaviour and reinforcing this action | Significant increase |

As we can see, the signs appealing to the sense of community and the threat of a fine showed no significant reduction. The most effective signs in this study were those based on the principle of observation bias – people behave differently if they think people are watching – and those with a positive reinforcement or descriptive norms. This along with the findings that the sign using negative descriptive norms actually resulted in a significant increase in littering, suggests that negative messaging is not effective when it comes to changing people’s behaviour around littering.

Putting it into practice

Ready to put your own sign messaging to the test? With all behavioural change interventions, it is important to test to see if it’s effective in different locations and for different audiences – what works in one place with a certain group of people may not have the same success in a different location.

All behaviour change initiatives should be tested to make sure they are most relevant to the target audience. Firstly, you will need to get baseline data for the littering issue before putting up the signage – or having a ‘control’ area which has no signage.

Then once the signage is up, the volume of littering over a set timeframe is compared. When comparing, consistency is a top priority, which means looking at a weekend before the sign went up and then the following weekend, rather than comparing a Monday with a Saturday for example. It’s also recommended that any trials aren’t publicised in advance as this may result in observer biases from people knowing that they are being monitored.

Conducting these types of studies into the impact of signs on littering also provides opportunities to collect other kinds of important data relating to plastic pollution. For example, the different type of litter can also be collated, recorded and used to feedback to local businesses to encourage the introduction of reuse schemes and championing refill messaging.

So remember, littering can be reduced in your local area with the following initiatives:

1.More bins in littering hot spots, with recycling bins in the same place

2.Introducing a local reusable cup scheme

3.Controlled testing of signage and messaging to see what works in your local area

Good luck! Let us know how you get on in your local area by tagging us on social media.